![]()

Aaron Roth – HOPE International – July 2011

- Download this email as a pdf: Aaron Roth – August 2011 Update.pdf

- Blog and Support Page: www.AaronRoth.net

- HOPE International Worldwide – www.HOPEinternational.org

- Newsletter Archive: AaronRoth.net – Monthly Newsletters

I was sitting in a broken chair, sweating as usual, in the office of a school director, Colasa Baez de Leon, whose school is in our micro-lending program and I asked her about the community where this school resides. I had to travel outside the city of La Romana to a tough neighborhood via motorcycle taxi to get here. She pauses for a moment and begins the story this way, “Sometimes the students come up to me around 4:00pm and say, ‘Director, may I leave school? I haven’t eaten and I need to go home so that my mom can prepare me some food.’” She looks at me with the honesty of a mother caring for her own children and says, “How can you not feed a hungry child?”

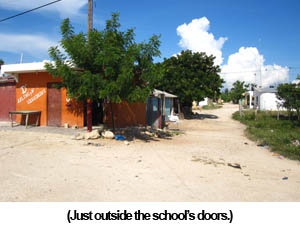

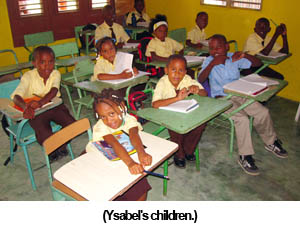

In another meeting, I commented to Ysabel Garcia Hernandez, the director of a much smaller school, “It seems to me that you really love these students.” She warmly responded, “Oh yes, of course. They are my children. If they weren’t in school, they’d be on the street.” I looked out across the dusty, rocky, unpaved road and I know she’s waiting for me to say something, but all I can do is just smile and nod in affirmation.

In another meeting, I commented to Ysabel Garcia Hernandez, the director of a much smaller school, “It seems to me that you really love these students.” She warmly responded, “Oh yes, of course. They are my children. If they weren’t in school, they’d be on the street.” I looked out across the dusty, rocky, unpaved road and I know she’s waiting for me to say something, but all I can do is just smile and nod in affirmation.

The Line that Separates Two Worlds

I have never thought that I would ever see such clear distinctions of the consequences of poverty as I have seen here. I am shocked to think that these are the kind of distinctions that walk the fine line of either having money to buy food or going hungry, of being able to afford school, or spending your childhood on the street. Maybe sometimes in the States we treat our financial options as shades of gray, “If I make the decision of not eating out at a restaurant just once less per week, I can save a greater percentage of money toward my vacation fund.” Or, “If I lived closer to work I wouldn’t have to spend 40 minutes commuting and I’d probably save at least $100 on gas. ” Never do we face questions of black and white such as, “Will I still be able to eat if I buy this?” or “With my monthly expenses, will I be able to send my children to school? ”

The kind of distinction I have seen here is the difference between night and day. I have realized that in communities like this, often there is not electricity, so when it’s nighttime it’s actually really dark. (Even though that observation sounds trite, think about what it felt like the last time a storm knocked your power out. It was really, really dark right?) When I had come back from this trip to the schools, I talked to a Dominican colleague in the office and tried to use a translation of the phrase “difference between night and day,” and she explained to me that normally here they’d say “The difference between Heaven and Earth. ” Hmmm, that’s interesting, I said to myself while considering these two statements:

The kind of distinction I have seen here is the difference between night and day. I have realized that in communities like this, often there is not electricity, so when it’s nighttime it’s actually really dark. (Even though that observation sounds trite, think about what it felt like the last time a storm knocked your power out. It was really, really dark right?) When I had come back from this trip to the schools, I talked to a Dominican colleague in the office and tried to use a translation of the phrase “difference between night and day,” and she explained to me that normally here they’d say “The difference between Heaven and Earth. ” Hmmm, that’s interesting, I said to myself while considering these two statements:

Colasa feeds the children at her school from her own kitchen if they haven’t eaten by 4:00.

Ysabel provides scholarships to 10 students that cannot afford the $7 monthly tuition.

Truly, this is a difference between Heaven and Earth.

To better illuminate this distinction, you need to know that most of the Dominican economy runs on the “informal economy” which best can be described as the “daily hustle.” Daily hustle is the sound of market vendors yelling out daily offers where the loudest v oice gets the most customers.

oice gets the most customers.

It’s also the tangible fear you feel when you step off of a street curb as bus drivers swerve through the lanes to reach a destination before the other buses or public cars because the fastest driver gets the most passengers. It’s the early wake up call when walking salesmen pitch household goods to neighborhood dwellers at 6:30am. True, they’re waking you up early, but at least you were just sleeping, most of them got up more than an hour ago, because the successful ones are the strongest that get up the earlies0,t and can walk through the most neighborhoods.

If you’re not loud, if you’re not fast, if you’re not strong, you get left behind. That’s just how it is. These are the laws of the world, the laws of the hustle. It’s not, “get rich or die trying” it’s “stay alive hustling, or die hustling.” There is no other option for the poor.

Love in the Hustle Economy

So then why in the hustle economy have people like Colasa and Ysabel chosen to serve the most needy, the most weakened and the most vulnerable? As anyone will tell you here, in the hustle economy, anybody who slows you down puts you at risk for your own demise. You’ve got to run with the strong and fast or your own survival is in jeopardy.  But for these women, they have a rebellious nature. They don’t believe in the hustle economy. These seemingly innocent women are clearly, and unashamedly, rule breakers. So when I asked them why they bend “the rules”, they responded:

But for these women, they have a rebellious nature. They don’t believe in the hustle economy. These seemingly innocent women are clearly, and unashamedly, rule breakers. So when I asked them why they bend “the rules”, they responded:

“Because Jesus has walked with me my whole life. He is my rock.” – Ysabel

“Jesus came to Earth, to save us, and to serve us. He gives me the strength to serve.” – Colasa

In the harsh rules of the hustle economy these women have recognized that we all lose if we live by the rules of the world. We all die if we leave others behind, but we all win when we love. Love is the trump card that ensures prosperity. In a counterintuitive sense, this new law has proven for them, time and again, that when we break the rules with love, our security is guaranteed. These are women that truly understand this truth:

“But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.” – Matthew 6:33

I pray that you and I will seek a kingdom that is greater than the ruling laws of the modern economy or the hustle economy.

Dios les bendiga,

-Aaron

aroth@hopeinternational.org

www.AaronRoth.net

Skype: aprothwm05